Sarah Charlesworth

David Deitcher

A look back at the artist’s quintessential postmodernism.

Sarah Charlesworth, installation view. Photo: Steven Probert.

Sarah Charlesworth, Paula Cooper Gallery, 524 West Twenty-Sixth Street, New York City, through March 23, 2019

• • •

In 2014, a year after Sarah Charlesworth’s untimely death at age sixty-six, Maccarone mounted a show of her best-known series, the Objects of Desire (1983–88). Employing photographs culled from a range of publications (fashion magazines, fanzines, archaeology books, etc.), the works feature an image extracted from its context and reshot against a deeply saturated monochrome ground. Untethered and sumptuously proffered, Charlesworth’s “objects” leave viewers at once seduced and estranged.

Charlesworth’s estate is now represented by Paula Cooper Gallery, which gives us a back story to the Objects of Desire in an exhibition focusing on the artist’s earlier practice—one linked to what, in the early 1980s, was called “critical postmodernism.” It’s a term I know well; I came of age as an art historian at the same moment when, and milieu in which Charlesworth began her career. Just as this show retraces the artist’s initial formation, reviewing it means retracing my own. Indeed, much of what I understand about postmodern art I first learned by looking at Charlesworth’s early photographic works.

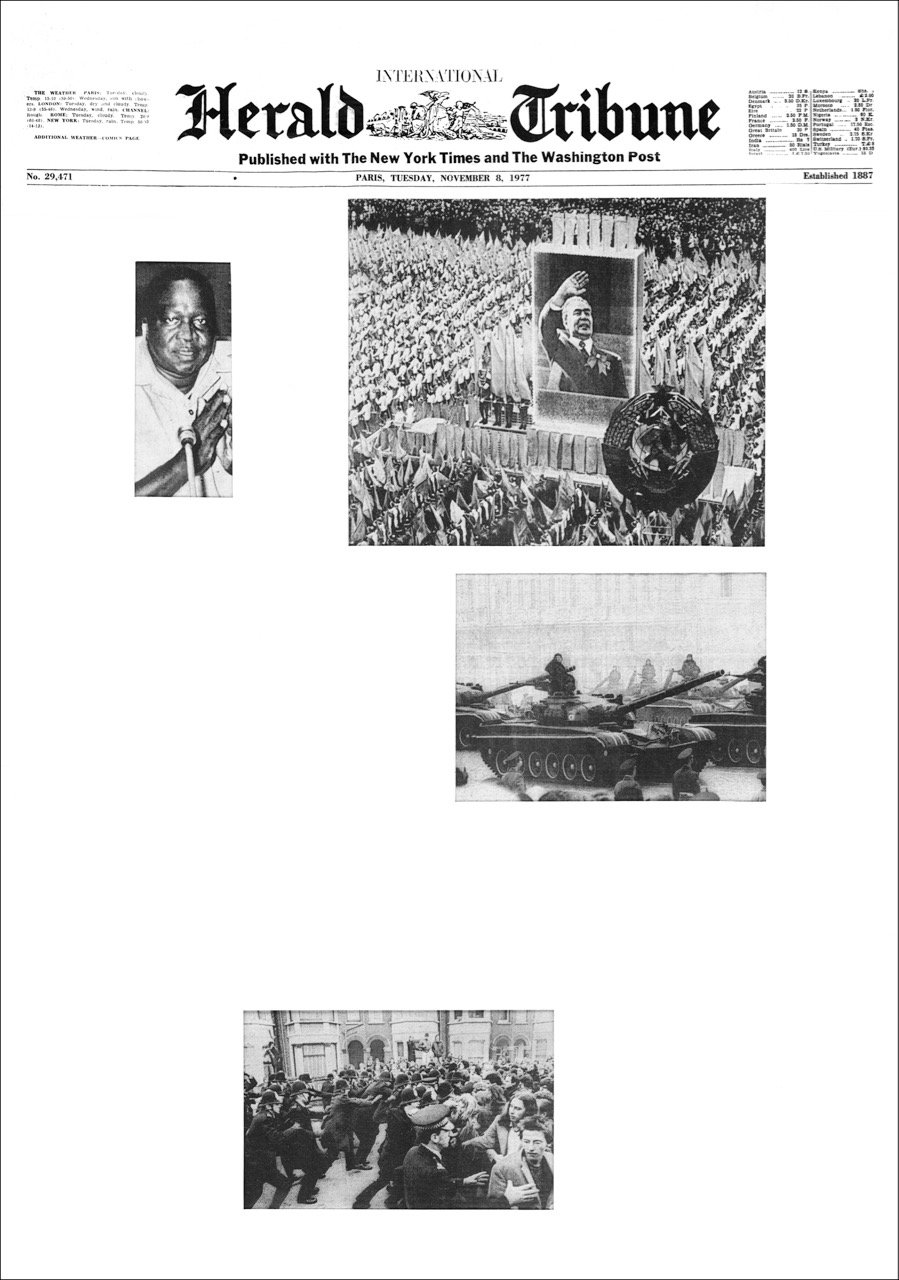

Sarah Charlesworth, Herald Tribune, November 1977, 1977. 26 black-and-white prints, 23 ¾ × 16 ½ × 1 ¼ inches each. © Estate of Sarah Charlesworth. Image courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery.

Appropriation, deconstruction, and the critique of representation: these are the quintessential postmodern strategies I discovered in the pieces now on view at Paula Cooper. One finds all three at play in her Herald Tribune, November 1977 (1977), a work that epitomizes Charlesworth’s austere, early photo-conceptualism. Occupying the length of a spacious gallery, the piece comprises twenty-six panels. Each shows a full-sized picture of the newspaper’s front page from a particular day in November 1977, from which Charlesworth hand cut all copy before reassembling the layout, using only pictures and masthead, and substituting white space for the excised text. Cut up and reassembled to reveal latent meaning, Charlesworth’s front pages are models of deconstruction. Stripped of accompanying text, the images tell a distilled story of what made news in 1977, and arguably still does: white men, dictators, and the occasional royal.

The works Charlesworth titled In-Photography (1981–82), a number of which are featured here, also reveal her critical engagement with pictures. She aggressively tore or surgically cut apart appropriated images, and lay the shards against black or white grounds, then reshot and printed them, greatly enlarged, as photomontages. She mounted this assault on photography’s once all-too-seamless, mythic verisimilitude “to make room for myself,” she stated in 1984, and “to disrupt the closure of an intensified known.” The conflict between photography’s historical claim to credibility and such challenges to it operate like a motor principle throughout Charlesworth’s oeuvre.

Sarah Charlesworth, installation view. Photo: Steven Probert. Pictured: Cube #2, 1981 (left) and Spiral Galaxy MGC4565, 1981 (right).

Some of the artist’s tears and incisions rhyme visually with her source material, as in the aggressively torn Explosion (1981). A similarly aerated blowup, Spiral Galaxy MGC4565, is redolent of the big bang. In response to a picture of Toshiro Mifune brandishing a sword (Samurai), Charlesworth made similarly swooping slashes, albeit using a smaller blade. Other cuts are more densely poetic. There are two chairs in Rietveld Chair. A cutout of that canonical design serves as the aperture through which one sees a room containing a different Rietveld chair. To this black-and-white photomontage, the artist added yellow gel accents and a red-and-blue lacquered frame, primary colors that contribute to an art-historical condensation—distilled De Stijl.

Sarah Charlesworth, installation view. Photo: Steven Probert. Pictured: Japanese House, 1982 (left) and Rietveld Chair, 1981 (right).

The show includes only one Still—the name Charlesworth gave to her monumentalized pictures of individuals plummeting to what most of the photographs more than hint was certain death. Unidentified Man, Unidentified Location (#3) (1980) shows what appears to be a construction worker falling, head first. Almost forty years later, after the events and iconography of September 11, 2001, such images read more dreadfully than ever. Unidentified indeed, I think; and divested of all humanity. But what if the appropriated picture is actually a production still, and its subject a Hollywood stuntman who—not unlike artist Yves Klein when he made that iconic leap into the void—landed safely on a tarp? The artist increasingly favored such uncertainty, an escape that her other Stills disallow.

Sarah Charlesworth, Unidentified Man, Unidentified Location (#3), 1980. Black-and-white mural print, 78 × 42 inches. © Estate of Sarah Charlesworth. Image courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery.

Charlesworth frequently altered images she found in books and magazines in response to the graphic designer’s sometimes hilarious sequencing. Consider the small, dazzling Cibachrome, Rider (1983–84). Against a vermilion background, the unmistakably masculine silhouette of a cowboy on a rearing horse frames a black-and-white glamour shot. Likely Natalie Wood, en décolletage, the image followed the cowboy picture in a magazine. Charlesworth applied the same Chinese red to the lacquered wood frame, and to three other similarly sized works (all 1983–84). Together, they herald, and here stand in for, the Objects of Desire.

Sarah Charlesworth, Rider, 1983–84. Cibachrome with lacquered wood frame, 20 ½ × 15 ¾ × 1 ¼ inches. © Estate of Sarah Charlesworth. Image courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery.

The development of these seductive pieces testifies to the artist’s turn away from her earlier, starkly critical aesthetic. No longer would her art deny allure, nor gloss over her involuntary attraction to the pictures she critiqued, which model masculinity, femininity, fashion, and taste. Rider’s cowboy-shaped aperture made it possible for Charlesworth to provide viewers with access to a picture that she claimed induced a “personal sense of oppression.” By literally foregrounding its patriarchal overdetermination in the form of a cowboy-shaped hypermasculine frame, she could live with her contradictory response to such an image. The four red works underscore this shift almost as forcefully as Objects of Desire.

The exhibition tracks Charlesworth’s creative evolution from direct criticality to uncertainty, seduction, and visual pleasure—an evolution that mirrors my thinking—but it also offers an important introduction to a decisive period in the development of postmodern art, as embodied in the work of a single artist. There is a long history of challenges to photographic veracity, to which Charlesworth and her colleagues—Barbara Kruger, Cindy Sherman, and Sherrie Levine—added a crucial, feminist element. These works remind me of the hopes my peers and I shared for the power of art to effect social change, progressively. As the weaponization of falsehoods and “alternative facts” escalates, there is an urgent need to learn from critical postmodernism, as activists have, to devise methods to undermine authority and counter the proliferation of toxic misrepresentation.