The Other Way

David Deitcher

Tim Rollins and K.O.S., The Bricks, 1982/83

In a 1996 video documentary about Tim Rollins and his student-collaborators, the Kids of Survival (K.O.S.), Rollins dramatically and succinctly describes the group’s process: “We begin by cutting up the text. We vandalize it, but we also honor it; and we end up making it our own.”[i] While some might disagree that the process begins with “cutting up the text” (as opposed, for example, to reading it first while the kids improvise), few would contradict Rollins’s characterization of the group’s unique relationship to the texts that they read, discuss, draw, paint, and otherwise “make their own.” [ii]

Rollins made a similar point concerning the art world’s supposed “opening up” to women and people of color during the 1980s. “I don’t think of it as an ‘opening up,’” he said. “No one did us a favor. We just broke in. Not everyone banged on the palace doors; many went through the back door. We walked in, pretended we were servants, and decided to stay for a while.”[iii] Embedded within both “breaking in” and going “through the back door” is an abiding belief in the efficacy of art, in combination with radical pedagogy, to empower underprivileged youth. This compelling as well as uplifting understanding emerged, as it were, organically from the group’s creative process and has informed most critical analyses not only of the Art and Knowledge Workshop’s mission, but also of the impressive works Rollins and K.O.S. have produced. In what follows, I intend to pull back somewhat from that understanding to consider some of the other ways in which important works by the group relate to the times, culture, and politics in which they created them.

Tim Rollins and K.O.S. The Red Badge of Courage IV (After Stephen Crane), 1986, oil on book pages mounted on linen, 21 x 36 inches.

Here is how Rollins has described the process that, beginning in 1986, led to the group’s monumental paintings based on Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage: “What I asked the Kids to do,” he reports, “was to paint a wound as if it was a self-portrait—but not a realistic-looking wound. It’s a wound of everything that your people have survived in the past, and that you as an individual are surviving in the present, and what you’re going to have to survive in the future.”[iv] In the video documentary, these words follow upon the Kids’ recital of brief passages from the book (for example, “He had dwelt in the strange land of squalling upheavals and had come forth . . .”). Together, the sequence demonstrates how the Kids identified with Crane’s novel, which Rollins encouraged them to read as allegory. “It’s not about a war in the 1860s,” he maintains, “it’s really about the civil war that rages within every individual who chooses to fight life as it is.” Despite Rollins’s inclination to allegorize Crane’s narrative, the Kids may well have identified with the struggles of its protagonist, Henry Fleming, who survives the horrors of the Civil War and ultimately acquires in the process an appreciation for the power of solidarity, of “pulling together as a group” (“There was a consciousness always of his comrades about him. . . . It was a mysterious fraternity born of the smoke and danger of death”). The special-ed students who became Rollins’s early collaborators knew a great deal about hardship and confronting discouraging odds, having been raised amid the poverty, privation, and random violence of the South Bronx during the early years of the Reagan era—to say nothing of the individual learning disabilities that sometimes added to their burden.

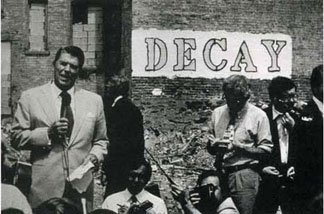

Most of them would have ranged in age between seven and nine in 1980, when then-presidential candidate Ronald Reagan staged an early photo-op standing amid the rubble of a vacant lot on Charlotte Street in the South Bronx. Photo-documentation of the event shows the so-called great communicator holding a mike in his right hand and a script in his left, as the press records his every word and gesture. On that day, Reagan appeared oblivious to (or deliberately to exploit) the presence directly behind him of a giant word (“DECAY”), which the guerrilla-artist John Fekner had stenciled in huge letters on the brick wall of a neighboring building. Reagan stood amid flattened junk and bricks—the remains of the demolished buildings that once stood there. Two years later, Rollins and his students removed bricks from just such desolate lots, taking them back to their classroom where they conceived the first of many impressive poetic condensations: they painted each brick to resemble a burning tenement building like the ones from which each had fallen.

John Fekner, Decay, 1980

For the Red Badge paintings, the Kids painted their “wounds” on paper and applied them to a meticulous grid of book pages that they mounted, as in all their ambitious paintings since 1984, on stretched Belgian linen. The result was a monumental, all-over composition spotted with the colorful designs—blobs of color ranging from biomorphic to geometric, suggesting raw vulnerability, or shield-like medallions suggesting self-protection. But to this observer, the “wounds” always conjured the Kaposi Sarcoma lesions that then disfigured the faces and bodies of people with AIDS. Identifying these paintings with the AIDS crisis helps bridge the conceptual gap that separated the underprivileged residents of the South Bronx from their more affluent counterparts in the downtown art world. For as AIDS activists argued throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, this blood-borne, sexually transmitted epidemic cut across socioeconomic lines, establishing common ground between the lives of middle-class, mostly white gay men and those of the differently disenfranchised people of color who constituted the epidemic’s other principal risk group.

The Red Badge paintings also bring to mind Ross Bleckner’s contemporaneous black paintings of the mid-1980s (themselves among the earliest artists’ responses to AIDS) in which sickly greenish strokes of paint that share space with ornamental embellishments and funerary iconography such as wreaths and urns reminded some of K. S. lesions.

Tim Rollins and K.O.S., A Journal of the Plague Year (After Daniel Defoe), 1987-88, animal blood on book pagesmounted on linen, 97 x 85 inches

No less susceptible to the inspirational reading of the group’s project, other works from the mid-to-late 1980s referred more directly to the health emergency. Beginning in 1988, the group addressed head-on the epidemic, its public policy implications, and its framing iconography in a series of works based on their reading of Daniel Defoe’s 1722 novel A Journal of the Plague Year. Considering that the South Bronx was likely the most impoverished congressional district in the U. S., beset, moreover, with one of the nation’s highest rates of HIV infection, and that at least one K.O.S. member (Carlos Rivera) learned that his mother was HIV-positive and feared that he might be too, the group determined to pull together and address the crisis to understand its actual causes, to combat the mystification, panic, and prejudice surrounding AIDS, and to provide symbolic means of managing its terrible emotional toll. British critic Marko Daniel has identified a number of parallels between Defoe’s fictional account of the Great Plague in seventeenth-century London and “prevalent public attitudes [during the 1980s] towards AIDS.” Daniel notes, for example, the unreliability of data as “residents who have been infected . . . are not yet showing symptoms,” an observation not from Defoe but in fact from The New York Times. Daniel also quotes directly from Defoe regarding the use of symbols in seventeenth-century Europe to ward off infection. “Papers tied up with so many Knots, and certain Words, or Figures written on them, as particularly the Word Abracadabra, form’d in Triangle or Pyramid.”[v]

Centered on an expansive grid of book pages, the Plague Year paintings feature an inverted pyramid of lettering (its typeface derived from a Roman tomb) that repeatedly spells “ABRACADABRA,” the cabalistic word that, as Defoe noted, was thought to have magical powers to keep the Plague at bay, especially when inscribed in blood in the form of a triangle or pyramid. Encountering that word writ large in lamb’s blood on a ground composed of pages from Defoe’s book had a starkly different effect in the late twentieth century, when it read as a caustic metaphor for not only the widespread governmental refusal to address the epidemic scientifically and humanely, but also the toxic mystifications of religious fundamentalists such as Jerry Falwell, who declared AIDS God’s punishment of gay men; and the Roman Catholic Church’s opposition to the use of condoms to prevent HIV transmission. “The sign Abracadara does nothing,” writes Daniel, “to fight, heal or prevent the spread of a disease. It identifies victims and ‘marks’ them, stigmatizes them.”[vi]

The Silence = Death Project, Silence = Death

Indeed, the inverted pyramid employed by Rollins and K.O.S. refers to the ultimate stigmatizing “mark” of gay men: the inverted pink triangle that the Nazis used to brand homosexuals in and out of the concentration camps to which they sent thousands of them. Rollins and K.O.S. also responded to Plague Year in 1988 with an edition of small works in which they again used lamb’s blood to paint an inverted triangle on single pages from Defoe’s book. The resulting works therefore evoked the blood-borne nature of the virus, the Nazi’s use of an inverted pink triangle to brand homosexuals, and also the reversal and rehabilitation of that Nazi emblem by gay liberationists, culminating in the 1986 Silence=Death Project’s black poster with its bright pink pyramid—now pointing upwards—over the equation “Silence=Death,” an image that became the galvanizing emblem of the AIDS activist movement.

These were not the only times when Rollins and K.O.S. used animal blood as an ingredient for creating works of art to respond topically to a literary classic. They also used it to powerful effect in paintings and prints based on Flaubert’s Temptation of Saint Anthony, as they had in an early work based on Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Such sensitivity to the symbolic as well as material properties of organic substances relates such projects to the groundbreaking works of the Italian Arte Povera movement; it also brings to mind Group Material’s Timeline: Chronicle of US Intervention in Central and Latin America (1984) in which the artist’s collective (in which Rollins then still participated) installed quantities of coffee and tobacco leaves, a reference to Arte Povera that also underscored precisely what was at stake in such American meddling in the affairs of other sovereign nations.

The celebrated “golden horn” paintings from the Amerika series, inspired by Franz Kafka’s novel, also harbor discreet and direct references to AIDS and to the violence it unleashed against those it affected most directly. The upper left corner of Amerika VII, (1986-87) is dominated by a satellite-like form that represents the morphology of HIV, derived from an illustration on the front page of The New York Times Science Times section of March 3, 1987. The painting also includes a depiction of Louise Bourgeois’s phallic Janus sculptures, and depictions of coiled lengths of spiky thorns borrowed from Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece. Painted during the spring of 1987, Amerika VII corresponded with the formation of ACT UP/New York—that is, with the crystallization of the AIDS activist movement, and in retrospect implies Rollins’s personal solidarity with that movement. Such solidarity would have been complexly determined. In addition to the anger that he shared with virtually everyone he knew about the government’s failure to address the health crisis, to say nothing of the politics, prejudice, and injustice that informed it, Rollins was deeply concerned about the well being of his youthful collaborators. And as a man who had sex with men, he would also have been susceptible to the terror and anxiety regarding his own health.[vii]

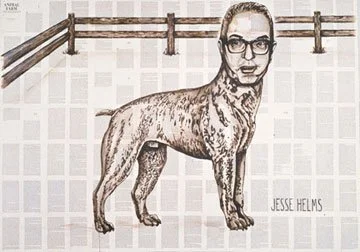

Tim Rollins and K.O.S., Jesse Helms from The Animal Farm (after George Orwell) 1987, acrylic and graphite on book pages mounted on linen, 55 7/8 x 80 1/8 inches

The paintings that Rollins and K.O.S. executed in response to George Orwell’s Animal Farm assume central importance within any consideration of the political and artistic implications of the group’s project. They worked together to learn about world leaders and about national and international politics, ultimately demonstrating their determination and entitlement to speak truth to power. Rollins says that the Animal Farm paintings have given people “a hard time” because of the propagandistic logic of identifying politicians and heads of state with so many barnyard animals. That said, this zoomorphic brand of caricature has illustrious roots that date back beyond even such eighteenth- and nineteenth-century exemplars as Thomas Rowlandson, J. J. Grandville, and Honoré Daumier. The first major Animal Farm painting gathers together Israel’s Yitzhak Shamir (a goat), South Africa’s Pieter Willem Botha (a rottweiler), Russian President Mikhail Gorbachev (a bull), British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher (a goose), and Ronald Reagan (a turtle). While one might debate who more deserves comparison with a rottweiler, Botha or Shamir, Thatcher’s head atop the body of a goose, or Reagan’s on a turtle leaves little mystery. Thatcher’s goose handily satirizes her absurd, faux upper-class British arrogance and hauteur, while the portrayal of Reagan as a turtle relates more directly to politics. When in 1987 members of ACT UP/NY installed Let the Record Show, in the Broadway window of the New Museum of Contemporary Art, their design featured a photomural of the Nuremburg Trials as backdrop to cutout photographic portrait-busts of six “AIDS criminals,” their notoriously AIDS-phobic and homophobic words inscribed before them in tombstone-like panels. This motley crew included Jesse Helms, Cory Servaas (of the Presidential AIDS Commission), an anonymous surgeon, Jerry Falwell, and William F. Buckley; only Reagan’s marker remained blank—blank because the president couldn’t bring himself to come out of his turtle’s shell, even to pronounce the word “AIDS,” until the death of Rock Hudson in 1985 made his continued silence about the health emergency politically untenable.

In 1992, Rollins and K.O.S. executed a gigantic (fifty-foot long), commissioned Animal Farm painting teeming with zoomorphically caricatured world leaders. A compositional tour de force, the work depicts the heads of state isolated by power not only from their constituents, but also, curiously, from each other. Creating this monumental work clearly entailed a great deal of research, enabling Rollins and the Kids to learn more about geography and world leaders than most people. Nevertheless, to this observer the most forceful Animal Farm works have always been the large-scale paintings focusing on one figure, such as the memorable portrayal of then-Senator Jesse Helms as a pit-bull who fiercely, if absurdly, stands his barnyard ground. Clearly the use of zoomorphic caricature was well suited both to the Kids and their mentor, helping them realize a variety of pedagogical and artistic goals. From another perspective, however, these works also bring to mind the uncompromisingly straightforward Portraits of Power that Leon Golub painted throughout the 1970s. The decidedly modest scale of Golub’s easel paintings, as well as his stylistic distortions, effectively de-monumentalized, in some cases humanized, and in many more instances satirized such larger-than-life, often heartless players on the world stage as Henry Kissinger, Richard Nixon, Nelson Rockefeller, Francisco Franco, Fidel Castro, and Mao Zedong. Given that during the 1980s Golub’s powerful paintings of menacing interrogators, mercenaries, and other bullies became highly visible, Rollins likely shared with the Kids his familiarity with them.

Leon Golub, Francisco Franco 1949 from Portraits of Power, 1976, acrylic on canvas, 17 x 17 inches.

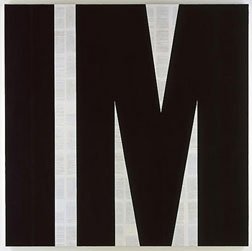

Tim Rollins and K.O.S., Invisible Man (After Ralph Ellison), 1998, acrylic on book pages mounted on linen, 72 x 72 inches

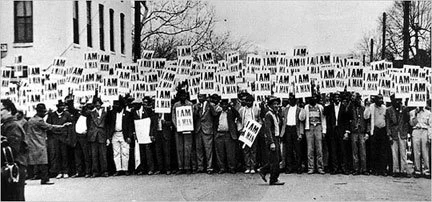

Painted in 1999, Invisible Man (After Ralph Ellison) is another one of the group’s elegant poetic visualizations of a classic, and in this case African-American, novel. Two towering white sans-seraph letters, “I” and “M,” dominate the painting, left and right. Each is composed of the cutout book-page ground under a thin wash of translucent white paint. Positive and negative fuse as the letters “I” and “M” are shaped by the black-painted surface that surrounds them. The group took full advantage of the fact that, when pronounced out loud, those two letters appoximate the historically charged phrase “I am a man,” and the many photographs that show it being carried by sanitation workers during the tumultuous 1968 Memphis Sanitation strike. Between February 11 and April 12, 1968, black sanitation workers responded to years of dangerous working conditions, discrimination, and the work-related deaths of Echol Cole and Robert Walker by walking off the job. Throughout those 64 days, their efforts to join the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSME) Local 1733, to secure wage increases and end discrimination attracted national media attention, guaranteeing the widespread dissemination of photographs showing the Black strikers and their supporters carrying posters emblazoned with the phrase with the verb “am” emphatically underscored. Among the supporters of the sanitation workers’ strike were Roy Wilkins, James Lawson, Bayard Rustin and the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who would be killed in that city on April 4, before the strike was settled.

The 1988-89 cycle of paintings that Rollins and K.O.S. executed based on Franz Schubert’s song cycle Winterreise made a profound impression when I first saw it in 1989 at Manhattan’s Dia Center for the Arts, in an exhibition principally devoted to the entire suite of eleven monumental paintings based on Kafka’s Amerika. Along a wall stretching almost sixty feet, the seventy panels composing this most extensive iteration of the Winterreise cycle receded in space. Each panel from the series consists of one page from Schubert’s score laid down on linen and stretched over a wood panel. As the group has applied to each successive panel an increasing number of layers of white acrylic paint, containing suspended flecks of mica, the score becomes less and less legible as the viewer moves from left to right. The experience evokes the sensation of walking through a winter landscape as snow begins to fall until, eventually, whiteout occurs, an uncanny visual equivalent for Schubert’s settings of Wilhelm Müller’s twenty-four poems addressing unrequited love and loneliness. Winterreise, displayed quite off to the side at Dia, provided this observer with a welcome respite from what Roberta Smith aptly called the “brassy, visual cacophony” that the Amerika series generated everywhere else on that floor of Dia’s West 22nd Street building.[viii]

Ernest Withers, Memphis Strike, Gelatin Silver Print, 1968

Over the years, I’ve often thought back to that first mind-blowing experience of Winterreise, and its impression has lost none of its power. On the contrary, as I only realized upon a later encounter with another, truncated version of the work, I had come to mistake the size of the panels, greatly enlarging them in memory when in fact each panel measures an intimate twelve by nine inches—the size of a single page from the score. This retroactive enlargement attests to the power of quiet, especially in relation to even the most exquisite noise.

My own enthusiasm notwithstanding, other critics tended to overlook Winterreise, perhaps literally not seeing it amid the virtuoso visual cacophony at Dia; or perhaps their critical silence implied their disregard for a work they considered too clearly and exclusively related to Rollins’s own taste for the European classics and too remote from the Kids, whose taste in music they may have presumed to begin and end with hip-hop. After all, Rollins’s most hostile critics have voiced skepticism regarding the refinement and sophistication of the group’s artistic output, which they reasonably attribute to Rollins. In discussions with some critical observers, such skepticism frequently joins with other, more toxic attitudes—namely, that while teaching the Kids, Rollins is also exploiting them.[ix]

In the absence of any generative critical responses to Winterreise, and being so powerfully drawn to the piece, I determined to explore the work more closely and discussed Schubert’s cycle with a music professor at Brown University. I asked whether Winterreise has figured in the tumultuous debate in musicological circles about Maynard Solomon’s groundbreaking 1981 article, “Franz Schubert and the Peacocks of Benvenuto Cellini.” Solomon had argued that Schubert, who never married and conducted no known romantic liaisons with women, but who did maintain passionate friendships within a circle of men, may have been homosexual. The response came that, no, Winterreise had not figured in that controversy. But the professor then directed me to song number XX, Die Wegweiser (the sign post). He suspected that its text, of all Müller’s poems, would be the most suggestive as evidence of Schubert’s alleged queer sexuality. After reading the poem and detecting a possible pattern in the group’s project, I decided to write Tim, resulting in the following email exchange:

Tim Rollins and K.O.S., Winterreise (Songs XX-XXIV)(After Franz Schubert), 1988, Acrylic and mica on music pages mounted on linen and board, 12 parts, 12 x 9 inches each; approx. 12 x 119 inches overall

Details

DD: The title page of the song called Wegweiser (sign post) appears more than once in various sets of the Winterreise paintings—for example, the opening panel of the set that currently figures in the Tang retrospective. Does/did that song/poem have special meaning for you? For the kids?

TR: The sign post is a metaphor for what we believe true artists use to, first, locate themselves in history and then make the decision to get lost in the wilderness of some new creation. This is so corny, but we’ve known it to be true.

Corny? Hardly. But Wegweiser also has significance beyond its pedagogical utility as a means of teaching young artists about the importance of situating one’s work historically, and then of pushing beyond such historical correspondence, which defines but thereby risks confining both artists and their works, and of the equal importance of moving on to “get lost” in the “wilderness” of uncharted territory.

Like any poem The Sign Post invites multiple interpretations, which are contingent on the reader in all of his or her complexity. Here, then, the poem translated into English:

Why do I avoid the highways

that other travelers take

and seek hidden paths

among snow-clad rocky heights?

Yet I have done no wrong

That I should shun mankind.

What senseless craving

drives me into the wilderness?

Signposts stand on the roads,

pointing towards the towns;

and I wander on ceaselessly,

restless, yet seeking rest.

I see a signpost standing there

Immovably before my eyes;

I must travel a road

from which no man has ever returned.[x]

Having said all that, I choose to finesse rather than pretend not to notice, two verses that seem to contradict this view: “Yet I have done no wrong/that I should shun mankind.” Wouldn’t the homosexual feel, on the contrary, that he or she has done a great deal wrong? I can resolve that apparent contradiction by recourse to the historical-constructionist understanding that in the early nineteenth century, when Müller composed his poems and Schubert set them to such achingly beautiful music, “homosexual” did not yet exist either as a conceptualization of same-sex love or as a way of categorizing same-sexers.[xi] For the queer to claim a composer of Schubert’s stature as one of our own is one way imaginatively to transcend the solitary fate of the social outcast by finding evidence of an illustrious cultural past with which one can identify. The compulsion to lay claim to a partly positive historical legacy, especially as such legacies have institutionally been denied or discounted, also informed Isaac Julien’s contemporaneous film, Looking for Langston (1989), which looked at Langston Hughes and the Harlem Renaissance from a queer perspective for just such a sense of cultural belonging and validation. That desire for a past parallels Rollins’s own determination that the Kids must lay claim to vaunted cultural traditions and practices of which polite society had declared them unworthy; that they should, rather, not knock on the palace door but slip in through the back door, whether or not that entails impersonating servants, and “stay for a while.”Within the context of Rollins’s project, there is no discernible reason to question his pedagogically oriented appreciation for the poem. But from the more private, or anyway personal, perspective of the gay or bisexual man or woman, the poem also assumes other, no less important meanings, since as it so beautifully evokes the situation of the outcast or outsider who, confronted by social directives, is compelled to go his or her own way, which is the other way; that way of the Other. As such, The Sign Post expresses the pain of the exile to which homosexuals have been consigned by societies and cultures still dominated by the ideological state apparatuses of the Church, the family and the law—in short, compulsory heterosexuality.

NOTES

[i] Rollins in Danya Goldfine, Dan Geller, Kids of Survival: The Art and Life of Tim Rollins and K.O.S. (video documentary, New York: Geller/Goldfine Productions, 1996).

[ii] Rollins’s characterization suggests the “antropofagia,” or “cannibalization” of European modernism that Brazilian Surrealists advocated during the mid-1920s to make such modernism their own. See Paolo Herkenhoff, “Introduao geral,” in XXIV Bienal de Såo Paulo, Núcleo Historico : Antropofagia e Histórias de Canibalismos, ed. Paolo Herkenhoff and Adriano Pedrosa (Såo Paulo: Fundacão Bienal de São Paulo, 1998).

[iii] Rollins quoted in “Tim Rollins Talks to David Deitcher,” Artforum 41, no. 8 (April 2003): 238.

[iv] Rollins in Kids of Survival: The Art and Life of Time Rollins and K.O.S.

[v] Marko Daniel, “The Art and Knowledge Workshop: A Study,” in Tim Rollins and K.O.S., exh. cat. (London: Riverside Studios, 1988).

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Rollins has only acknowledged his bisexuality publicly in recent interviews, though his queer sexuality had been an open secret for years, at least to all who knew him.

[viii] Roberta Smith, “’Amerika’ by Tim Rollins and K.O.S.,” New York Times (3 November 1989): C33.

[ix] Some respected friends are among those who view the refinement and sophistication of the group’s output with such skepticism, but the toxicity that can accompany that outlook was given its fullest, most destructive and irresponsible expression in a purportedly muckraking article in New York magazine in 1991. See Mark Lasswell, “True Colors: Tim Rollins’s Odd Life with the Kids of Survival,” New York (29 July 1991): 30-8.

[x] I have cobbled together this English translation from two sources: first, from a translation by William Mann (1985) from the liner notes accompanying a 1972 recording of Winterreise by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, accompanied on the piano by Gerald Moore, Deutsche Grammophon 4151872, 1985; second, from the subtitles for a performance by Fischer-Dieskau, accompanied on the piano by Alfred Brendel, posted on You Tube: http://vids.myspace.com/index.cfm?fuseaction=vids.individual&videoid=32980098.

[xi] See Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Volume I: An Introduction, trans. Robert Hurley (New York: Vantage, 1980) and Jonathan Ned Katz, The Invention of Heterosexuality (New York: Dutton, 1995). Also see my Dear Friends: American Photographs of Men Together, 1840-1918 (New York: Abrams, 2001)