Floating Boulders and Other Magical Acts

David Deitcher

Jim Hodges thought long and hard to come up with a title he considered well suited for his curatorial project at The FLAG Art Foundation—an installation of selected works by himself and the late Felix Gonzalez-Torres. (1) Puzzled by the enigmatic title, I should be forgiven the art historian’s reflex to associate “Floating a Boulder” with a painting by René Magritte, which in no way figured consciously in Hodges’ considerations. After all, it may not be that inappropriate in this context to be reminded of the Belgian Surrealist’s painting of a giant levitating boulder (the top of which is carved to conjure the proverbial castle in the sky), an improbable image in which the artist imagines the boulder defying the effects of gravity. (2)

“Floating a Boulder” brings to mind other, less dreamlike magical acts, such as Gonzalez-Torres’ minimalist-inspired use of commonplace, industrially manufactured objects—office clocks, stacks of offset prints, candies, strings of lights—which he deployed in ways that far exceed the meanings and functions of such objects, eliciting unexpectedly emotional responses in susceptible viewers. Thus the uncanny drama of paired, battery-operated office clocks (“Untitled” [Perfect Lovers], 1987-90); or the artist’s conception of the stacks and candy spills, which gradually disappear as viewers carry off their constituent parts, but which the artist conceived so that their owners can replenish them if they wish. In this way, such works address the nonnegotiable fact of life’s major and minor contingencies while also imagining the possibility of renewal. Hodges, too, has performed magically affecting acts: with flimsy little paper diner napkins, artificial flowers, biker jackets, used 501’s, soiled jockey shorts, brogues, camouflage, chain link, etc., he has produced evanescent works of art that evoke loss while providing the limited, yet not insignificant, consolation of pleasurably challenging aesthetic engagement.

Even if one did not know (as many do) that Hodges and Gonzalez-Torres were intimate friends, viewers could easily discern that fact while coming upon more and less closely related works by each artist. That impression of the profound connection between them intensified as visitors meandered from one part of FLAG’s space to another. Passing through the plastic beaded curtain (Gonzalez-Torres’ “Untitled” [Golden], 1993) that formed a glittering, fluid threshold across the entrance to the staircase connecting the ninth- and tenth-floor spaces, they discovered one of Hodges’ delicate curtains of artificial flowers screening the small landing to the left at the top of the stairs, where it hung near two works by Gonzalez-Torres.

In Blue, the curtain of silk flowers that Hodges chose to show at FLAG, dates from 1996, the year of Gonzalez-Torres’s death. Hodges installed it adjacent to one of Gonzalez-Torres’s more enigmatic stacks, “Untitled” (We Don’t Remember), 1991, in which the German statement “Wir erinnern uns nicht” (We don’t remember) appears dead center within a deep crimson rectangle that is itself isolated within a larger field of pure white. Yet In Blue is all about remembrance, and its presence here therefore wordlessly countered the nihilistic thrust of the German statement. (3)

In addition to the memorial connotations of flowers, In Blue also evokes Gonzalez-Torres’ affection for a pale blue color that he chose to suit his occasional inclination to delight in producing tough yet tender works that elude casual detection. I’m thinking specifically of the pale blue sheer curtain “Untitled” (Loverboy), 1989, which first figured as part of the same solo exhibition (Every Week There is Something Different 1991) at Andrea Rosen’s SoHo gallery where “Untitled” (We Don’t Remember) was first shown—albeit in the relative privacy of Rosen’s office. At FLAG, Hodges triangulated In Blue and the red-and-white stack by hanging adjacent to them one of Gonzalez-Torres’ black-and-white photostats, in which the two white lines of names, events, and dates running along its lower third also countered the stack’s allusion to historical amnesia with potent cues to historical memory: “Head Start 1965 L.A. Olympics 1984 Willie Horton 1988 Civil Rights Act 1964 / War on Poverty 1964 Trickle Down Economy 1980 L.A. Rebellion 1992 Freedom / Summer 1964 Montgomery Bus Boycott 1955 Watts 1965 EuroDisney 1992.”

How remarkable it was to see such works the way Hodges situated them to foster such generative interplay. Hodges may have done his friend a favor of sorts by revealing Gonzalez-Torres’ profound commitment to fathoming and giving poetic shape to the public as well as private contents of individual consciousness. This juxtaposition of seemingly disparate works by each artist provided one of many thoughtful groupings of works in an installation that elsewhere could be disarmingly forthright in its allusions to the friendship and aesthetic sensibility that these two artists shared.

Perhaps nowhere was that forthrightness more evident than in the pairing of Gonzalez-Torres’ “Untitled” (Go-Go Dancing Platform), 1991, with four of Hodges’ large-scale mirror-mosaic panels (2005–09), each with titles that incorporate the word movements. Like flattened-out disco balls, these panels, each with one rounded edge, dispersed prismatic sprays of light onto the walls next to where they hung.

The go-go dancer’s platform stood to one side of the space, not far from the gallery’s entrance, looking distinctly forlorn despite its perimeter of gaily illuminated lightbulbs. Perhaps the sense of melancholy induced by this combination of works, which suggested a memorial to the pre-AIDS disco era, would have been relieved by the sight of the muscular dancer, clad only in a silver lamé bathing suit and sneakers, who performed on the platform for a few unscheduled minutes once daily whenever FLAG was open to the public. Or perhaps the dancer’s presence would not only not relieve the sense of anxious retrospection that suffused this gallery, but would have intensified it. After all, this dancer danced in what viewers would have experienced as total silence, since his Walkman (or was it now an iPod?) played music that only he could hear. In this way, this work isolates the dancer from his onlookers in an extreme example of the simultaneous distance-in-intimacy and intimacy-in-distance that art historian Miwon Kwon has rightly identified as a “conjoining dynamic” that operates throughout Gonzalez-Torres’ work. (4)

Heralding the retrospective, memorializing aspect of this gallery’s installation at its threshold, Hodges hung Gonzalez-Torres’ “Untitled,” 1991, the silk-screen print that the Public Art Fund published and offered for sale to help defray the cost of realizing the artist’s first billboard design—the monumental black-and-white dateline piece that the artist conceived to mark the twentieth anniversary of the Stonewall riots with a randomly organized selection of names, events, and dates, all of which relate to gay history, culture, and politics, which sign painter Kevin O’Connell hand-painted in two lines of white letters and numbers near the bottom of the otherwise black expanse. (5) Appearing on a privately owned billboard above Sheridan Square (aka Stonewall Place) in a public setting traversed by such private interests less than one block from the site of the formerly Mafia-run Stonewall Inn, this public work employed a number of methods to expose the brittle permeability of the boundary between “public” and “private,” which gay men and lesbians have been positioned so well by church and state to mistrust. (6) Perhaps to undermine any singular reading of the nearby gallery’s contents (i.e., as “a memorial to the pre-AIDS disco era”), Hodges also inserted a small, menacing presence in the space—an unrelentingly single-minded small black photostat, “Untitled,” 1988, which packs a fearsome wallop despite its diminutive size. Its white dateline lists only the names and dates of lethal armaments that figure among the few remaining products of American industrial ingenuity; “B-2 Stealth Bomber 1982 V-22 Osprey Antisub plane 1983 / A-6 Intruder Fighter 1984 Aquila Drone (Remote-piloted) 1987…” etc. In the corridor outside that gallery, Hodges maintained the somewhat gloomy tone by installing his own lugubrious The Bells/Black, 2007, which shares in the interactivity of the works by his friend with removable and/or adjustable parts by tempting viewers to pull on the nylon bell cords to produce nonsonorous gongs.

Intimacy mostly trumped distance in the large tenth-floor gallery, where Hodges installed a range of works, all of them presided over by Gonzalez-Torres’ “Untitled,” 1989/95, his self-portrait that, like all of the artist’s portraits, assumes the form of a sequence of names, events, and dates like those on his black-and-white photostats, but that a sign painter executes by hand in silver paint. At FLAG, the self-portrait circumnavigated the gallery’s walls, friezelike, just below ceiling height. Like the photostats, which the portraits supplanted in 1992, the self-portrait’s dateline employs the formers’ nonlinear sequencing of names, events, and dates. Consistent with the artist’s wish (systematized, as always, in the works’ certificates of authenticity) that the life of the portraits be sustained long after their subjects’ deaths, Gonzalez-Torres encouraged owners (in this case the Art Institute of Chicago and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art) to make changes to the original items on the dateline, as they deem appropriate. For its appearance at FLAG, Hodges added one new item to the portrait: “Death 1996.” (7)

On the long west wall opposite the entrance to this gallery, Hodges hung Gonzalez-Torres’ color photograph of flowers, “Untitled” (Alice B. Toklas’ and Gertrude Stein’s Grave, Paris), 1992, only a few feet away from his own intricately incised photograph of a tree shot against a sunny yet chilly-looking sky (London II [pink and blue], 2006–09). Emitting its own silvery light, this work rhymed visually with the self-portrait’s reflective paint. On the floor in front of these works, Hodges placed a rectangular carpet of green cellophane–wrapped candies (Gonzalez-Torres’“Untitled” [Rossmore II], 1991). This singularly verdant candy piece, presented here in two parts, is named for the street in Los Angeles where, in 1991, Gonzalez-Torres stayed with his lover Ross Laycock and Harry, their black Labrador retriever, in a furnished one-bedroom flat at the funky Ravenswood Apartments during Gonzalez-Torres’ one-semester teaching job at CalArts. (8) Hodges installed a mound of the green candies in one corner of the adjacent (“dining room”) space, where he also installed one of his own delicate accumulations of drawings on paper diner napkins (A Diary of Flowers [Just Blue], 1993). On the gallery’s north-facing wall, Hodges installed Gonzalez-Torres’ “Untitled” (19 Days of Bloodwork—Steady Decline), 1994, one of a number of deeply affecting variations on Agnes Martin’s graphite grids.

Near the south-facing windows, Hodges provided visitors with a space to retreat and reflect, or anyway to relax in comfort with a modicum of privacy, by installing his own A Good Fence, 2008. This pine enclosure, replete with hinged gate, was large enough to enclose a pair of couches (part of FLAG’s own furnishings) that faced each other (north/south) from opposite sides of a coffee table on which Hodges placed a vase of stargazer lilies that were almost as fragrant as the pine enclosure itself. Hodges calibrated the installation so that anyone seated on one of the couches could see part of the self-portrait and part of the photograph of Stein’s and Toklas’ flower-planted gravesite over the top of the fence. But viewers did not need to look even that far to find one of Gonzalez-Torres’ works. Inside the enclosure, Hodges hung a small 1988 photostat with a dateline that begins “ New Life Forms Patents 1987 Ollie 1986 / Anti-Frost Bacteria 1987 MTV 1983…,” its historical cues again bringing public issues to bear on a private situation.

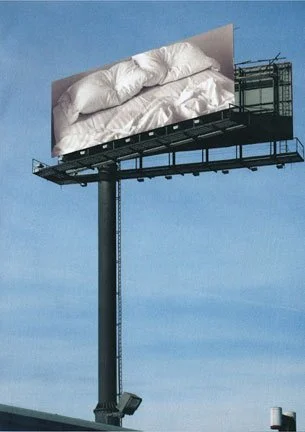

One need only consult another catalogue of Hodges’ works (say, the handsome one from the Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum at Skidmore College) to get a sense of the breadth of his output over the years, as well as of the editorial effort that he must have expended to single out a suitable selection of his own works to correspond with his selection of works by Gonzalez-Torres. These he cogently mobilized not only in FLAG’s space but also on two billboards in Manhattan and two each in Queens and the Bronx. As of this writing, New Yorkers have the opportunity once again to look up and see the uncaptioned image of a queen-size bed with rumpled bedclothes and two pillows, each indented with the impression of the head of the person who had lain there. That well-known and much-loved billboard has lost none of its haunting luster since it was last seen in New York nearly a decade ago. (9) In such ways, Floating a Boulder provided an opportunity for viewers to see an intimate selection of important works by two remarkable artists in dialogue. The project provided Hodges with an opportunity as well to revisit and extend the dialogue he maintained with Felix during his lifetime; a chance to return to his powerful sense of connection to the cherished friend whom he lost. Inasmuch as this dialogue now occurs across the threshold that separates here from there, now from then, life from death, it recalls and enacts one of the more important tropes that Felix returned to more than once: in stacks that bear the parenthetical title Passport, and in the paired mirror installation “Untitled” (Orpheus, Twice), 1991. To this observer, no less magical than floating boulders in the sky.

NOTES

1 “when working on a title for the exhibition i went through the same process as i always go through when looking for the words to attach to work. with ‘floating a boulder’ i felt extra pressure to ‘get it right!’ since the words would be associated with both felix’s and my work. once many years ago felix complimented me on my titles saying, ‘jimmy, you and roni have the best titles.’ it meant a lot to me but also added to the anxiety about giving this project a meaningful name that would live up to his expectations, (a bar he had set high for me many years ago). i had to find the words that could contain both his and my respective practices and as a matter of fact it was by focusing on each of our practices that i came to these words. on one of those early morning realizations after days and maybe weeks of contemplation, frustration, obsessing on the subject, i awoke with those words on my mind … the elusive image or condition that they conjured in me felt perfect… obscure and yet specific and weighted… something alluding to magic and overcoming the impossible, bringing to mind intentions, belief, power and awe….” Jim Hodges, e-mail to the author (December 4, 2009).

2 In this context, it is worth remembering Gonzalez-Torres’ interest in a revealing, if puzzling, statement by Carl Andre: “My sculptures are masses and their subject is matter.” Gonzalez-Torres follows this quotation by insisting on the feminist rationale for his own way of identifying Minimalist sculptures with more resonantly quotidian objects. (“For me they were a coffee table,” Gonzalez-Torres described his free associations to Minimalist sculpture, “a laundry bag, a laundry box, whatever.”) See Tim Rollins, “Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Interview,” in Julie Ault, ed., Felix Gonzalez-Torres (Göttingen, Germany: Steidldangin, 2006), 74

3 Andrea Rosen and Jim Hodges both maintain that Gonzalez-Torres understood the German statement in two ways, the second of which would be, “We do not remember ourselves.” But erinnern is a reflexive verb, and a German speaker would never use it to mean what Jim and Felix evidently thought that it also meant.

4 See: Miwon Kwon, “The Becoming of a Work of Art: FGT and a Possibility of Renewal, a Chance to Share, a Fragile Truce,” in Julie Ault, 281.

5 During a meeting at FLAG just prior to the opening of his installation, Hodges introduced me to Kevin O’Connell, who was in the process of painting Gonzalez-Torres’ self-portrait in the large tenth-floor gallery. They both also informed me, to my great surprise, that Kevin had hand-painted the white dateline on the billboard over Sheridan Square.

6 See my “How Do You Memorialize a Movement That Isn’t Dead?” in Ault, 201–3

7 Hodges has noted that he had also proposed adding “Obama 2008,” but that the Art Institute preferred to retain its own “Election Night Grant Park 2008.” In retrospect, this seems a wise choice, given the Obama administration’s mismanagement of the process of reforming American health care.

8 “Harry the Dog 1983” was the fourth item in the self-portrait’s first iteration (at the Brooklyn Museum, 1989), and has since been deleted. Soon after Felix and Ross left the Ravenswood, I moved into the same apartment (also for one semester’s teaching at CalArts). There I found that a band of black dog’s hair had accumulated where the apartment’s beige wall-to-wall-carpeted floors met the beige-painted walls. When I first saw the Rossmore-related candy piece, it was in the form of a long, narrow, wall-hugging strip of the green cellophane–wrapped candies, and it reminded me not only of the similarly narrow strip of grass that lines Rossmore Avenue’s sidewalks, but also of the strip of black dog’s hair lining the walls of the apartment where we all had stayed.

9 In fact, to some the billboard now looks even better than it originally did. As Felix often did, he foresaw and embraced the fact that billboards would change—not only in terms of their imagery at any given time but also in terms of contemporary techniques of display. The medium listed for the billboards in the artist’s Catalogue Raisonné always laconically states “billboard.” This left such works open to historical contingencies and kept the billboards alive, not unlike the portraits. Between 1992, when it first appeared as the Museum of Modern Art’s Project 34, and 2009, those techniques did change. The billboard is no longer a gigantically enlarged half-tone blow-up of a black-and-white photograph, but a high-resolution print on vinyl. It glows now as it never quite did before..